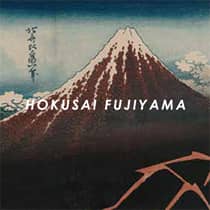

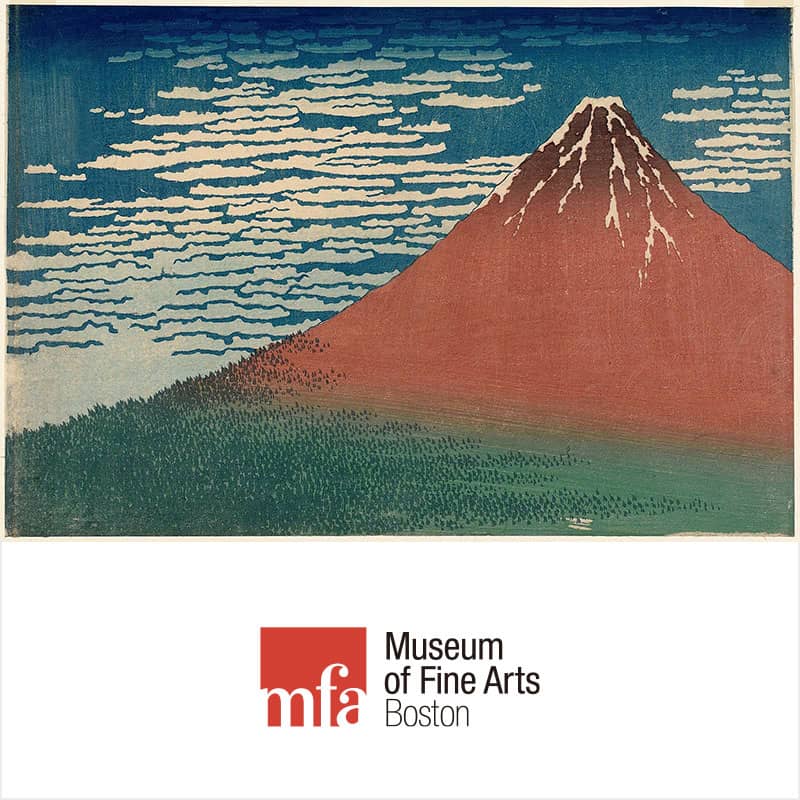

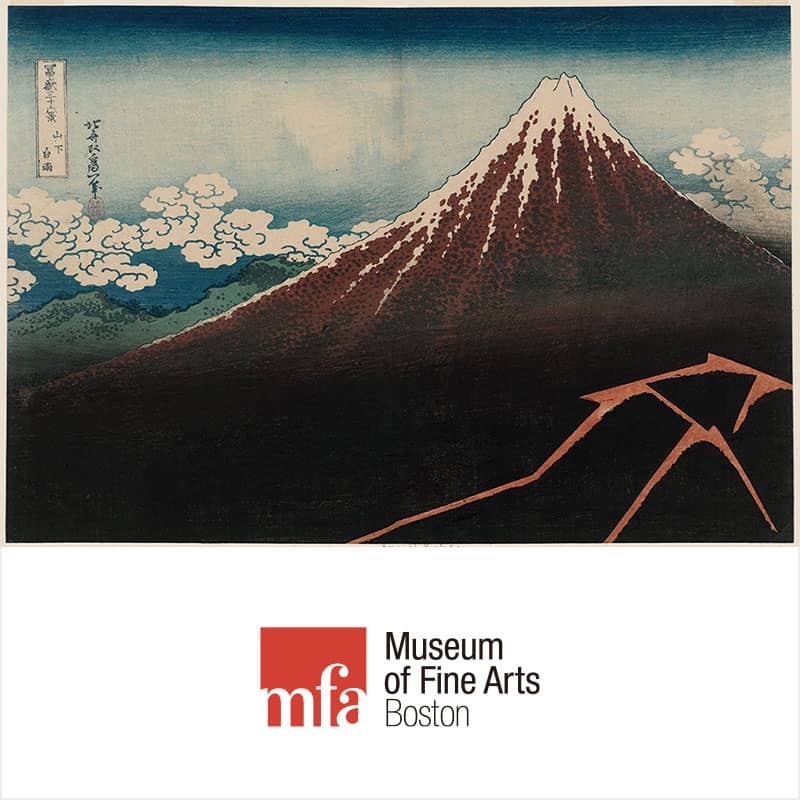

Naoki Ishikawa frequently captures Mt. Fuji in his photographs. This image he took from a canoe in Suruga Bay has a similar composition to Katsushika Hokusai’s “Fine Wind, Clear Morning”— one of his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

The innumerable faces of Mt. Fuji. Photographs and text by Naoki Ishikawa

I once climbed Mt. Fuji from sea level. I began my trip from Suruga Bay, rowing a canoe to the mouth of the Fuji River. From there, I traveled on foot to the start of the nearest hiking route and then climbed to the top. For three days, I saw Mt. Fuji and felt it with my hands and my feet. And every day, its colors and shapes morphed as it showed me different faces.

Distant views of Mt. Fuji—as seen in ukiyo-e, tourism materials, and the media— have come to symbolize Japan. But the closer I got to the mountain, the more it changed, becoming less and less familiar.

I climb Mt. Fuji over thirty times a year. In the summer, it is a black, desolate rock crawling with mountain climbers. The forest at its foot comes alive with springs bubbling and serows and other wildlife dashing through the labyrinthian woods.

In the winter, howling winds and thick layers of ice make Mt. Fuji unapproachable for both humans and animals. Only the most skilled climbers can reach its snowcapped top; for all others, the roads are closed off.

From the sea, Mt. Fuji appeared to me like a mirage floating above the waves. I didn’t get to see the mountain peeking from behind towering waves like Hokusai did, but the Mt. Fuji I saw from the placid, mirrorlike surface of the bay had the same sense of presence as in his work.

Many people have seen Mt. Fuji from the air while flying on a plane. I once took a helicopter to get a close look at the mountain’s crater. It was like gazing at another planet. As I photographed Mt. Fuji, becoming disoriented from the high altitude, I thought I saw the mountain’s many faces staring back at me. And yet, each face unmistakably belonged to one of the most recognizable mountains in the world.

Every year at the end of summer, this Mt. Fuji palanquin is paraded during the Fujiyoshida fire festival.

There are signs everywhere in Mt. Fuji of what the mountain meant to people in the past— holes and caves at the foot of the mountain where religious practitioners once stayed, climbers circling the cater at the top in a practice derived from religious ritual, and dozens of torii gates and miniature shrines. Numerous eruptions failed to dent its beautiful conic form—and so it came to be worshipped as a home of the gods, a place for religious practice, and a destination for pilgrimages. The local fire festival is a testament to this history.

Held at the end of summer in Fujiyoshida, a city at the foot of Mt. Fuji, the fire festival begins during the day with a Mt. Fuji-shaped palanquin—decorated in eye-catching red lacquer—paraded through town. It is a ritual symbolizing how Mt. Fuji has been an object of worship and a familiar presence in the lives of the Japanese throughout history. At night, the palanquin is placed in a designated location, and fires are lit across town. With all roads closed, the city blazes undisturbed—a magical sight. Fujiyoshida is home to Fuji Sengenjinja, a shrine dedicated to Mt. Fuji and located at the start of one of the mountain’s hiking routes. The fire festival allows the people living at the foot of Mt. Fuji to connect with this holy mountain both spiritually and physically.

Although peak bagging has become a popular activity, Japan’s mountains—both short and tall—were traditionally climbed for religious purposes. Even in Hokusai’s time, most people visited Mt. Fuji in group pilgrimages. Mt. Fuji, which Hokusai depicted with a typically Asian sense of animism, continues to remain popular among the Japanese because it reminds them of their roots, of the way their ancestors worshipped mountains.

Kitaguchihongu Fuji Sengenjinja is a shrine in the city of Fujiyoshida dedicated to Mt. Fuji, which was once worshipped as a home of the gods and attracted religious practitioners and pilgrims.

We still worship Mt. Fuji today, but in a more contemporary fashion—by wearing it on our T-shirts.

PROFILE

Naoki Ishikawa | Ishikawa was born in 1977 in Tokyo. His award-winning photobooks include Corona (2011; winner of the Domon Ken Award), as well as Marebito (Visitor) and Everest (both 2019), for which Ishikawa received the 2020 Photographic Society of Japan Lifetime Achievement Award.

Katsushika Hokusai | The famed ukiyo-e artist (1760–1849) produced numerous works in his lifetime, including Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and Hokusai Manga. The former popularized the use of Prussian blue pigment in Japanese artworks—it is for this reason that the color is sometimes referred to as “Hokusai blue.”