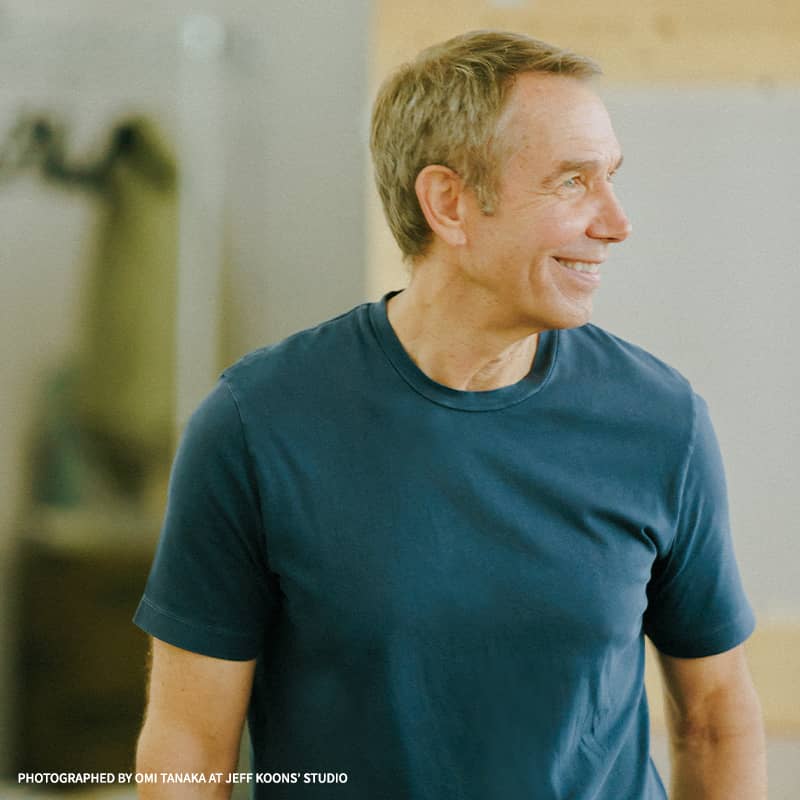

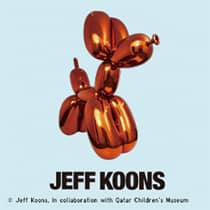

This fall, UNIQLO is releasing a collection of UT T-shirts designed by Jeff Koons, one of the most famous artists in the world today. From elevating everyday objects to groundbreaking larger-than-life sculptures dripping with high-octane color, to vibrant paintings and memorable installations, Koons’ career spans decades of exploring commodity, spectacle and the metaphysical.

He spoke to Sarah Hoover, art historian, writer and former director at Gagosian gallery, where she built her career for almost fifteen years. Together, Sarah and Jeff discussed the transformative power of art, Koons’ personal ideologies, and his next endeavor to be even more global, on the heels of his upcoming exhibition in Doha, Qatar.

Sarah Hoover:The myth of Jeff Koons is so highly developed. When I started in the gallery world, there were these legendary stories told about you: front desk assistant at MoMA and Wall Street broker selling art about commodity culture to the really rich guys you used to work with.

I don't know how much of it is made up and how much of it is true, but how much of that myth is intentional? Do you care about your own perception? In my mind, everything about you is meticulous and perfect and planned, but maybe you're actually completely insouciant and don't care at all. That's what I'm curious about.

Jeff Koons:I would have to say I'm aware of some of the mythology that, over the years, has surrounded myself and my work. I can understand how some of it came about. I was involved in sales at the Museum of Modern Art. Then, I became a broker. My work deals with the readymades. I work with everyday objects. But in many ways, I feel as though I've been a circular object forced into a triangular-type hole. It's not a perfect fit. I think people were interested in commodity culture and writing about it and would try to tie my work to, maybe, certain perceptions of that culture.

I've only ever been interested in “becoming,” and communicating people's sensations and feelings, and really, the power of art. How art can help us transcend and better our lives.

SH:Something that has been really powerful about the art world, actually, is the community that it's brought, I'm sure, to your life, and to mine. It's made up of some of the most eclectic and disruptive and brilliant thinkers. Of course, there are so many barriers to entry for so many people, like money, skin color and education being just a few.

When you were getting started in your career, as part of the artist scene in SoHo, and with so many legends, what was it like to be emerging? Do you think it's the way that it is to be an emerging artist today, or did it feel very special?

JK:I come from a rural background. I grew up in Pennsylvania. When I went to art school, I really didn't know anything about art. I had my first art history lesson in art school and my life changed. I realized that art so easily would connect us to all the different human disciplines: philosophy, psychology, theology.

When I went on, I continued studying art. I moved to Chicago and studied with the Chicago Imagists, and eventually, I moved to New York. The only thing I ever had an interest in—and my generation, the people that I was surrounded with—was the continuation of the idea of the avant‑garde.

That we can transform who we are and who we can become. Not only that, but you can also change the world around you. This idea of experiencing life and feeling the power of what we can become, that's what I picked up from the generation before us, like Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Lichtenstein, and the generation before them, Duchamp and Picabia—even as far back as Leonardo.

Everybody is interested in the same thing. It's about giving it up to something other than the self, really finding interest and curiosity in life. Then, contributing to the best of your abilities with your own generation. I really enjoyed being a part of mine.

SH:That's very positive. I suffer from imposter syndrome that is really deeply ingrained. Have you ever had moments where you've lacked that confidence in yourself? Are there practices you have to stay in that strong, positive, creative headspace so that you can keep creating your art?

JK:My first day of art school, we went to the Baltimore Museum of Art. When I walked around the museum I realized I didn't know anybody. I didn't know who Bracques was. I didn't know Matisse's work. I didn't know Cezanne. I would have known Picasso, maybe Dalí, but that really would have been it.

Then, we went back to school and we had our first art history lesson. They were telling us, “look around, because only a third of you are still going to be here two years from now.” I realized that I survived that moment. A lot of people don't survive that moment. They become very, very intimidated by art. They think that you must bring something to the table. This is life in general. They feel like you have to be prepared for something, have more knowledge about something, to participate in a dialogue other than your own past.

That's not the case. You have your own history. It can't be anything other than what it is. If we can only learn to accept ourselves, what our past is, and that we are perfect for where we are at this moment, it can't be any different than what it is. It's about this moment forward.

I accepted my limitations. I learned how to accept myself but to continue to try to become the best artist I can be—the best human being I can be. It's that desire to participate, to be a part of the whole, that is really what has guided me. I just want to be part of the dialogue, and to be as generous as I can be. You can't do anything more than that.

SH:I think something that people assume about you from the scale of your work—we touched on this briefly a second ago—is that it's about consumerism or the meaning of money, and maybe a critique of business and how the art world commodifies something, even as pure as sculpture. But your work is strikingly not elitist. I mean, what is more appealing than something like a balloon dog to practically everyone in the world, right? How do you reconcile the elitism of the art world that we all participate in with your personal ethics that focus on the universal?

JK:I think there are misconceptions that happen about people's work. John Dewey explains life in this way. Life is as simple as just a single‑cell organism interacting with its environment and the effect that environment has on that organism. Then in return, the effect that the organism has on the environment. That's communication. That's the life experience. That's what I'm involved with.

I'm involved with trying to have a dialogue about our internal life, our internal being, and the external world. I work with very plasticized-type objects, very three‑dimensional, external objects. Art is not in these objects. Where art is found is within our own being.

The objects we interact with, the things we come across in life, they can stimulate us. They can excite us, but that's not the art. The art is when we have an essence of our own potential. That's the art. If you're in a museum, that walks out of the room with you. If you're at a concert, it leaves with you when you leave that concert. Art is the essence of your own potential.

SH:Money is a taboo topic and I'm sorry that I keep touching on it, but you are undoubtedly one of the most successful artists of all time. I'm sure that your approach to making things shifted as you had more affluence in your own life.

I know that you've been willing to spend it all for your art and do anything it took to make your projects become reality, which is really incredible and singular. I wonder if money and your access to it has impacted your interest in making things that are more accessible to more people, like something that could be bought at a museum gift shop?

JK:I have to say that money never came into the equation. I always wanted to be able to support myself, have experiences in life, be able to take care of myself and make my work. The idea, the pursuit of money, that isn’t what you find joy in. You find joy in making something powerful that you'd look at and say, “wow.”

That's always been my interest. I ended up making things that would deal with the sense of perfection to a certain degree—and of quality. It's because I came to realize that one of the ways I could communicate trust to the viewer was to use craft and detail.

In dealing with the details, similarly, maybe you'll hear about Steve Jobs and about how the inside of the computer and the inside of the phone, everything is designed with this sense of perfection. I always had the same interests. It was that if anybody ever looked at one of my pieces, looked at the bottom of a work, or looked at something from a different angle, they would never be let down. They would realize that I cared about that experience. That's the way you can communicate to the viewer that you care about them.

In the end, we don't care about objects. They're inanimate. They have nothing to do with us. What is relevant is that we are biological beings and that we're able to continue to be, in some manner, supportive of each other, that we can continue to adapt and to flourish.

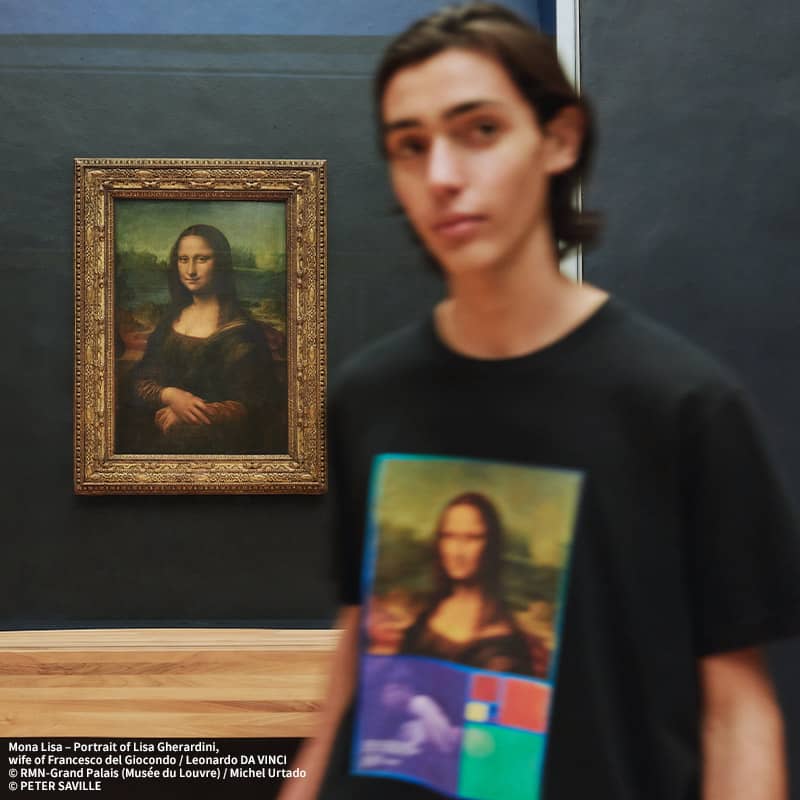

SH:I think what you're saying is so particularly UNIQLO in a way, because I know that their purpose is to create the highest quality of experience for the greatest number of people on Earth. That's direct language from them.

I know that a real goal for them is to improve people's lives, from their products to their stores, to the way they entrench themselves within local communities. I believe that philosophy is called Lifewear for them.

What you were just describing feels very much at home within that philosophy to me. Your work with these nearly universal icons as monumental sculptures—ballerinas, balloon dogs, and all that—also feels rooted within that philosophy. Did you have a sense of that when you decided to work with UNIQLO?

JK:I enjoy very much how UNIQLO is in contact with my generation but also a younger generation. It really communicates across cultures and everybody enjoys their clothing. I love that sense of unity and the way they embrace cultural issues. I think that's wonderful.

At the end of the day, we're just people who are seeking to be connected with each other. Any way that we can do that, by working with UNIQLO, making a T‑shirt that can be connected and communicate to somebody else that I care about them, or that we're interested in issues that are global, and that we're one. I embrace that opportunity.

SH:This is the Qatar-USA Year of Culture, and your 60‑work retrospective titled “Lost in America,” is opening in Doha this fall, so congratulations! I know that a portion of the proceeds from this T‑shirt is being donated to the museum, which is such a lovely way to give back. Was that important to you?

Also, the title of the exhibition is striking. It’s a time in which I think a lot of people are questioning the real identity of America, with a lot of cultural shifts happening. Is the title about that? I mean, do you even consider yourself an American artist? Is that an important classification for you? You’ve shown your work internationally for many years—I wonder if you feel it is distinctly American in any way.

JK:Yes. I've had a wonderful relationship with Qatar over the years. I started going to the country back in 2000. I've seen the growth taking place in Doha and within the country. I visited many of the different institutions.

It’s exciting to be able to work with the community to generate interest in art and try to have, again, this global dialogue of what art can be across cultures and how we all can realize that art isn't a defined thing, other than what I believe, coming into contact with the essence of our own potential.

And I love to be involved with working with children. It's really fantastic to have the opportunity to work with Qatar, in Doha, with the Children's Museum. Everybody, a new generation, is going to find their own way within art. They're going to experiment and see how meaning can be found to help the needs of new generations to come, to see how art can be a vehicle to better our lives. What could be more joyful and more rewarding than to participate in this program?

It's also very meaningful for me to represent America in this moment of A Year of Culture, this cultural exchange. It's a tremendous honor. The title of the exhibition...I think that it gives a sense of the different directions one can feel in America, from the time that I was born, back in the mid‑1950s, up to the present moment.

This exhibition was put together with Massimiliano Gioni, who I've worked with many times over the years. We've created different exhibitions together but Massimiliano came up with the title and I think it's a fantastic title.

SH:UNIQLO is a brand based in Tokyo. While they entrench themselves very purposefully in local communities through tremendous support of the arts, the sleek design and emphasis on quality feels particularly Japanese. Have you traveled a lot in Japan? How has your experience in that country been?

JK:I love Japan. My first trip to Japan was for an exhibition around 1990. I've been to Japan several times since then, and the most wonderful thing is the people. Just the generosity of the people and how supportive they are. They really want to be kind to each other. I love that aspect. I love the aesthetics of the Japanese people, and I love the poetry.

If I think about the ideas in my own work, and I speak about transcendence and the whole spiritual base of my work, there's a very Eastern Asian aspect to it, a Japanese aspect, to the heart of, really, what's relevant in life? What is really meaningful in life? How can we transcend our situation?

Over the years, I've continued to think about, what can you do? What do I do as an artist to connect? I came to realize that there's only one thing we can do—all of us, no matter what area of life we're involved with. And that's first, to have self‑acceptance. Once you have self‑acceptance, then you can stop looking inward but you can look outward.

The other thing is to follow your interests, because what else do you have other than your interests? What could be more joyful than that? Every person, if you trust in yourself and you follow your interests and you focus on them, it takes you to a metaphysical place where time and space bend and you connect to a universal vocabulary. This is what I practice every day.

PROFILE

Born in 1955, in York, Pennsylvania, Jeff Koons is a contemporary artist based in New York. Since his first solo exhibition in 1980, his works have been exhibited in major museums, galleries, and cultural institutions around the world, including Rockefeller Center, the Palace of Versailles, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. He has received numerous awards and honors in recognition of his cultural achievements. Koons is also known as a philanthropist; over the last four decades he has been involved with many causes while also serving on the board of the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children.

Jeff Koons, ‘Balloon Dog (Orange)’, 1994‒2000. © Jeff Koons, Photo: Tom Powel Imaging, Courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery, New York. In collaboration with Dadu, Children’s Museum of Qatar.

Jeff Koons, ‘Rabbit’, 1986. © Jeff Koons, In collaboration with Dadu, Children’s Museum of Qatar.

Jeff Koons, ‘Play-Doh’, 1994‒2014. © Jeff Koons, Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. In collaboration with Dadu, Children’s Museum of Qatar.

Jeff Koons, ‘Gazing Ball (Standing Woman)’, 2014. © Jeff Koons, Photo: Rebecca Fanuele, Courtesy Almine Rech. In collaboration with Dadu Children’s Museum of Qatar.

Jeff Koons, ‘Seated Ballerina’, 2010-2015. © Jeff Koons, Photo: © 2017 Fredrik Nilsen, Courtesy Gagosian. In collaboration with Dadu, Children’s Museum of Qatar.