It is the simple, everyday tale of the wishy-washy Charlie Brown and his imaginative dog Snoopy that has made Peanuts one of the world’s most beloved comic strips. UT’s new Sunday Special collection features panels from Sunday strips that depict the world of Peanuts in full color. Benjamin L. Clark of the Charles M. Schulz Museum talked to us about the humor in Schulz’s Sunday strips.

The Sunday Peanuts strip was a special one

There is something hopeful about the Sunday paper. Coverage of current events and politics is toned down, and comfort can be found in the prose of witty columnists, celebrity interviews, and comics. Like other comic strips, Peanuts runs as a black-and white daily from Monday through Saturday and as a full-color strip on Sunday. The pastel world of Peanuts has brought color and joy to weekend mornings since the comic’s Sunday strips began on Jan. 6, 1952. “Schulz was a passionate reader of Sunday comics growing up,” says Benjamin L. Clark, curator of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center in Santa Rosa, California. “The full-color spreads were the highlight of the Sunday edition, a feast for the mind and eye that inspired him to take up the pen himself.” Before long, Schulz himself was drawing Sunday strips for United Feature Syndicate, a distributor of syndicated comic strips to newspapers across the United States.

In the early 20th century, Sundays were the only day off for many workers. Newspapers competed for their attention and spending power by printing affordable entertainment in the form of comic strips and short stories. Sunday newspapers still follow this model today.

Clark explains that, although Sunday comic strips used to have nearly an entire

page each to tell their stories, by the time Schulz began the Sunday Peanuts strip in 1952, newspapers were printing multiple strips on one page. Even so, having space equivalent to three dailies stacked on top of one another allowed for more in-depth stories and more artistic freedom.

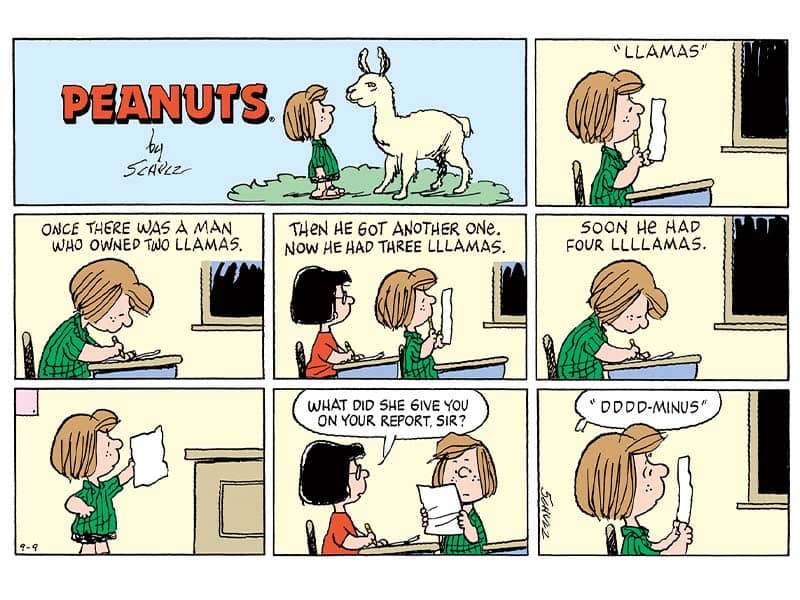

According to Clark, the title panels and throwaways of these three strips are unique. First up is a story about a llama, of all things. Says Clark: “An element of humor is in encountering the unexpected, for who would expect a llama in Peanuts? Readers cannot help but imagine what else may exist in this world. Schulz could really let his imagination run free in the Sunday title panels.” (Published Sept. 9, 1990)

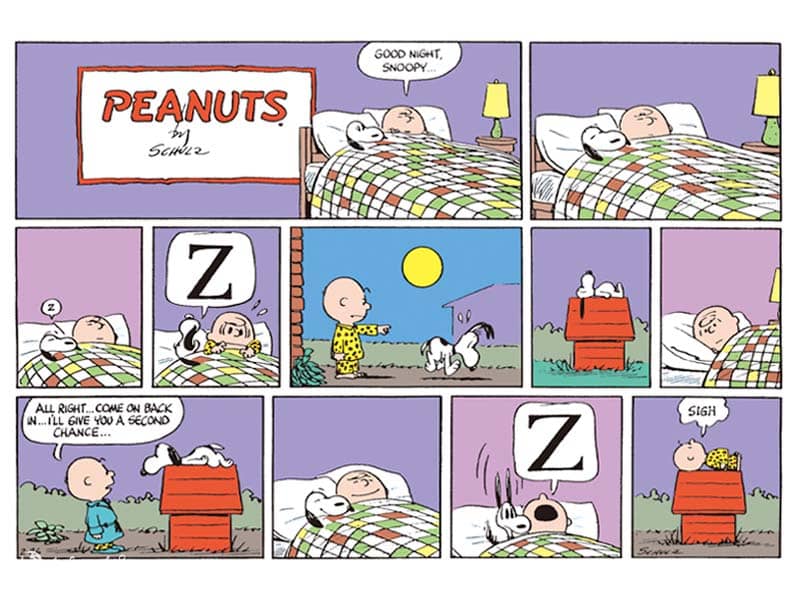

Schulz’s sense of humor is especially apparent in the title and “throwaway” panels—the first two panels of a Sunday strip. At the same time, Schulz also believed that “the last panel in a Sunday comic strip is especially important. When the reader first glances at the [comic], it is very easy for his eye to drop to the lower right-hand corner and have the whole [comic] spoiled. Thus, it is sometimes necessary to try not to attract attention to that panel, to make certain that the beginning panels are interesting enough to keep the reader from skipping to the end.”

Schulz juggled many such considerations, but Clark says that these were always motivated by Schulz’s love for newspapers and his readers. “Because newspapers are published in a few sizes, some papers have to format their Sunday comics differently.

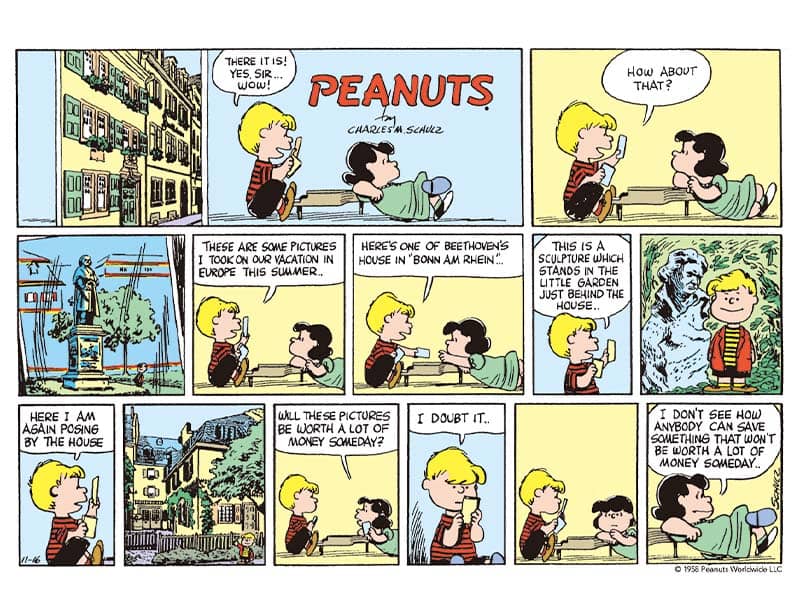

In this unusual strip, Schulz showed off his skill in perspective drawing. “His draftsmanship is an overlooked quality of his style, but it is something he took pride in,” explains Clark. “In title panels especially, Schulz was free to draw in a different style to communicate a complex idea—how do you depict a photograph within a strip?” (Published Nov. 16, 1958)

Cartoonists include panels that can be eliminated without losing any of the story or humor, but Schulz would often draw creative title panels and throwaways as a nod to those newspapers that kept his strip as he envisioned.”

In November 1966, Peanuts gained a subtitle: Featuring Good ol’ Charlie Brown. There is some speculation that this change came about because of Schulz’s well-known dislike of the name Peanuts.

“He called it ‘the most undignified name given to a comic strip,’” says Clark. “When the original title, Li’l Folks, was declined by legal advisors at United Feature Syndicate, Schulz suggested changing the strip’s title to Charlie Brown but was told they could not copyright such a common name.” In the end, the subtitle was featured on Sunday Peanuts strips until Jan. 4, 1987.

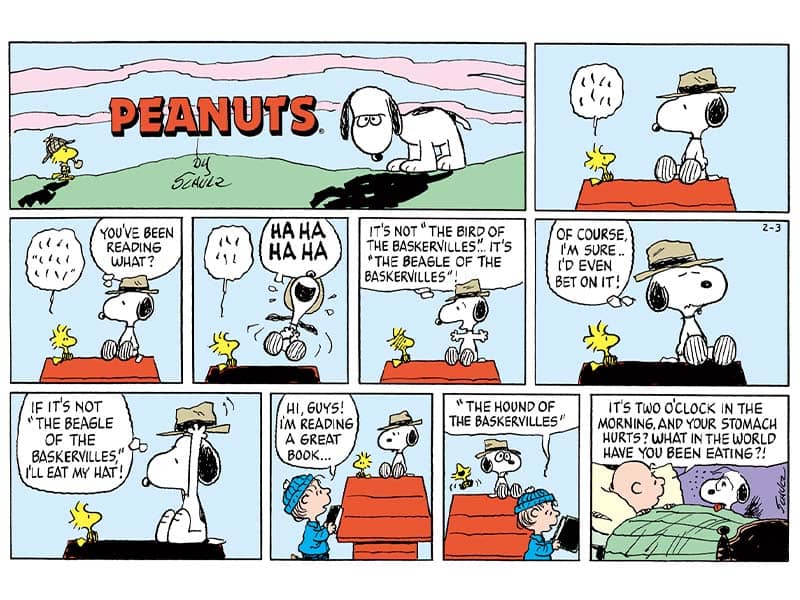

This title panel was inspired by Sherlock Holmes. “Woodstock dons Holmes’s deerstalker cap while Snoopy tries to impress the reader as the terrible Hound of the Baskervilles! Whether casting his characters in different roles or drawing something outside the world of Peanuts, Schulz’s sense of humor always comes through,” says Clark. (Published Feb. 3,

Schulz’s close attention to detail, from the strip’s name to how he approached his panels, demonstrates his extraordinary love for Peanuts. With the exception of a five-week break in 1997 to celebrate his 75th birthday, Schulz never took a day off before announcing his retirement in December 1999, only months before his death. In total, he drew 17,897 days’ worth of strips. How did Schulz stay motivated to keep going long after Peanuts became famous worldwide?

“Sometimes Schulz would be asked why he was still drawing comics after achieving so much success,” says Clark. “He would answer, why would he work so hard to do what he always dreamed of doing, just to quit once he was doing it?” From childhood, Charles Schulz dreamed of drawing comics—not only because they were fun but because he thought he could do it well. “He thought he could perhaps even draw the greatest comic strip of all time,” says Clark. “An artist will never achieve that type of greatness if they quit. His extraordinary dedication to his craft is part of what makes his achievements so remarkable.”

Benjamin L. Clark|Before becoming curator of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Clark’s career took him from his native Nebraska through Texas, Oklahoma, and Montana. Now, his team cares for and interprets the legacy of Charles M. Schulz.

The Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, is not far from where Schulz spent the last years of his life. Schulz himself oversaw the museum’s design and layout, and his mark can be seen throughout.

The Snoopy Museum, the only official satellite of the Schulz Museum, opened in 2019 in Tokyo’s Minami-Machida Grandberry Park. Laugh and Smile, a new exhibition commemorating the centennial of Schulz’s birth, will run until Jul. 10, 2022.

The Snoopy Museum | Adult admission: ¥1,800 (bring the coupon in the back of this catalogue for a ¥200 discount) Address: 3-1-1 Tsuruma, Machida City,Tokyo Phone: 042-812-2723 Hours: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (no admission after 5:30 p.m.) Open every day. (Call to confirm schedules)

PROFILE

Peanuts | Written and illustrated by Minnesotan Charles M. Schulz, Peanuts was first serialized in seven US newspapers on October 2, 1950, and ran until Schulz’s death in 2000. Even today, some 2,200 newspapers in 75 countries print Peanuts reruns in 21 languages.

©︎2022 Peanuts Worldwide LLC