The Walt Disney Company, a longtime collaborator of UT, is celebrating its centennial in 2023. Disney100 celebrates how wonder and magic transform moments into memories that last a lifetime. The collection explores the company’s history, giving a glimpse into how some of Disney’s most beloved characters have evolved over time. John T. Quinn III, a character art director with more than 25years of experience, speaks about the enduring appeal of Mickey Mouse and his friends.

Becoming an “actor with a pencil”

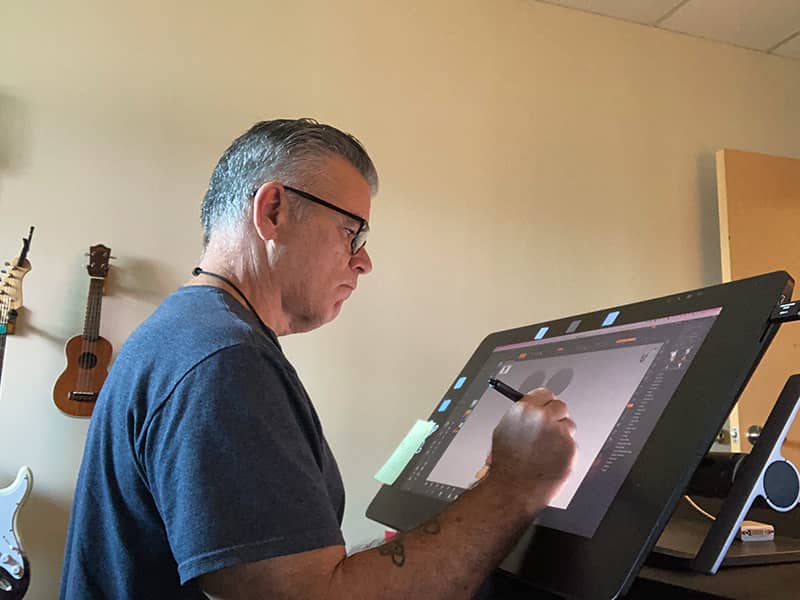

John T. Quinn III was raised on Disney movies. As he grew into adulthood, this childhood love inspired him to study illustration at art school and eventually join The Walt Disney Company. Quinn has been at the forefront of Disney Consumer Products for decades, but what was it like when he first began working there?

“Soon after I began my career with Disney, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston (two of Disney’s legendary Nine Old Men) were invited to come speak to the creative team,” says Quinn. “At the time, I believed that the ability to draw well was necessary to succeed at Disney, so I had been working hard to improve my drawing skills. I anticipated that their talk would be a validation of all that I had worked to achieve, that they would speak about drawing or reveal secret drawing techniques. Instead, they spoke about character, story, and acting. These two artists performed various skits and improvisations to demonstrate their method for understanding how the characters would act in unique situations. It was of course my talent for drawing that helped me get my foot in the door, but that day they revealed to me that I would have to become ‘an actor with a pencil’ if I was to make the kind of contributions I dreamed of.”

The talk by Thomas and Johnston was a life-changing experience for Quinn. It would not be enough for him to simply draw Mickey Mouse; he would need to find ways to put Mickey Mouse into interesting situations that would lend themselves to good stories.

“That is what we still do today,” Quinn says. “We carry on Walt Disney’s legacy by thinking about the story we are telling and how it will resonate with the audience while always striving for quality in our presentation. That’s why Disney movies have stood the test of time.”

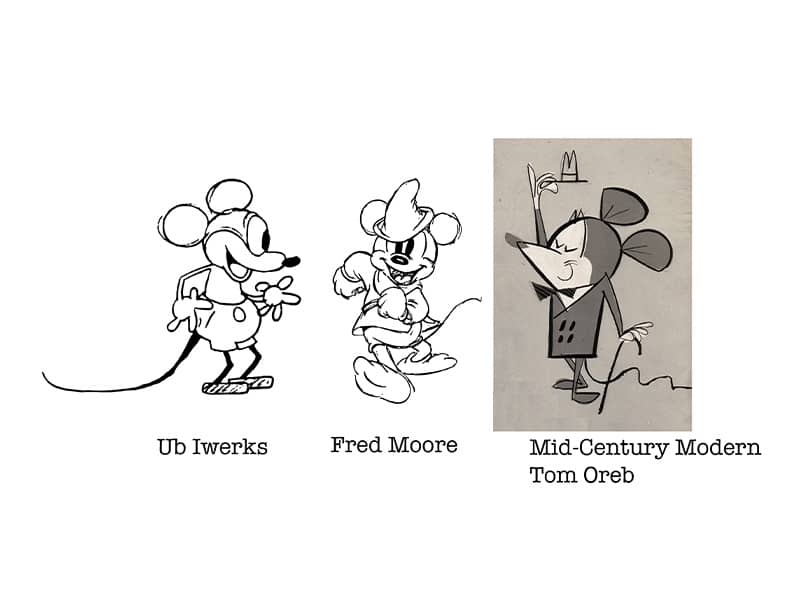

Like other Disney characters, Mickey Mouse has looked subtly different over the decades since his debut. One of the designs in this UT collection features several different iterations of Mickey. As a Disney artist, Quinn is intimately familiar with how Mickey Mouse and the other Disney characters have evolved.

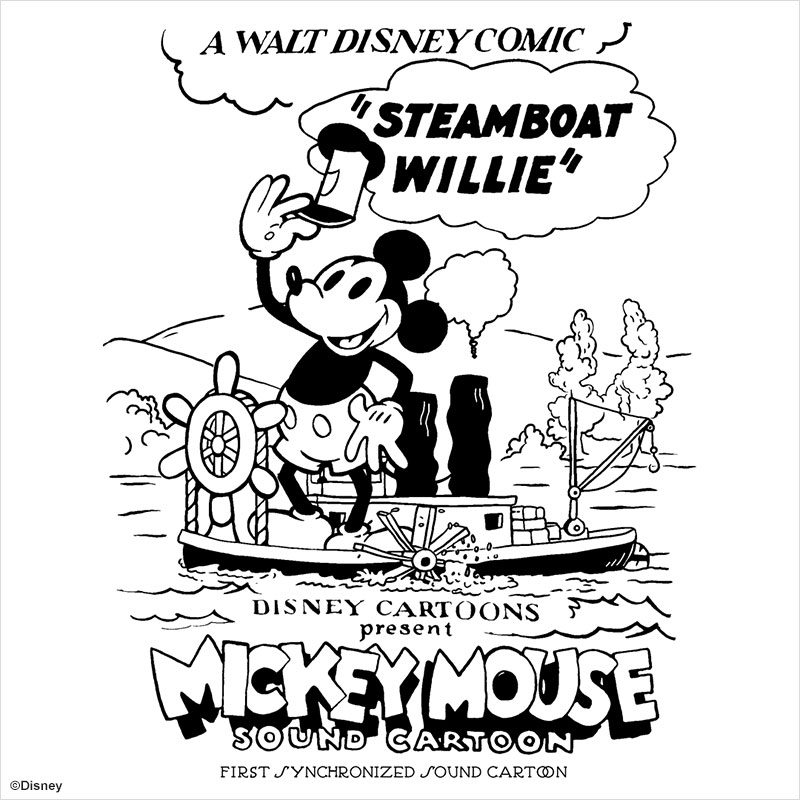

Early Disney films had very simple character designs consisting of one circle representing the head and one circle representing the torso. After adding blocks for feet and circles for hands and connecting them to the torso with hoses, all that was left to do was to add eyes, ears, and a nose to the head. Films were populated by barnyard animals like dogs, cows, rabbits, and mice, with the shape and size of the ears, nose, and tail often all that distinguished one character from the next. Artists used so-called “rubber hose animation” to animate a character’s actions, stretching and moving only the arms rather than the whole body.

“Animation as an art form was still in its infancy,” says Quinn. “The artists were always experimenting and learning, incrementally advancing their power of expression. However, technical limitations, such as the need to shoot on high-contrast black-and-white film, meant that movements as well as designs had to be simplified.”

In the late 1920s and the 1930s, technological advancements allowed animators to adopt new character design styles and introduce more fluid shapes. The invention of new animation principles—notably “squash and stretch”—led to innovations in the design of Mickey and Minnie Mouse and the types of movements that could be applied to them. When Mickey spoke in early cartoons, only his mouth would move. As techniques developed, however, artists began to animate his entire face and head to emphasize the emotions behind the dialogue. Walt Disney and the other artists at his studio pioneered many such basic animation principles in this era, which still inform the work of animation studios today.

Later, in the late 1940s and into the 1950s, character designs were influenced by contemporary art and design. This shift, as well as continuing advances in animation technology, resulted in character designs that were simplified and flattened, becoming more graphic and less volumetric.

One of the designs in this collection is taken from the Mickey Mouse comic strip, a syndicated series drawn by Floyd Gottfredson.

“For 45 years, dating all the way back to the 1930s, Mr. Gottfredson was the artist behind the comic strip,” says Quinn. “His drawing style evolved over the years. This particular design is from the 1930s, a time when Mickey and Minnie appeared in a variety of action and adventure stories about cowboys in the American West and pirates on the high seas, as well as in suspenseful crime dramas. Mr. Gottfredson always drew the characters in an appealing way that told a clear story.”

Finally, Quinn describes what it is like to work at The Walt Disney Company. “I work side by side with incredibly inspirational and talented artists and designers and have traveled around the world to partner with Disney teams in Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong, London, and Milan,” he says. “Each interaction I have with people across the globe helps inform and enrich both me and my work.”

PROFILE

John T. Quinn III | Born in New Jersey in 1964, Quinn first encountered Disney animation when he watched The Aristocats at the age of six. He joined the Walt Disney Company after graduating from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he studied illustration. He has worked on many Disney projects as a character art director.

Release dates and prices may vary. Some items might be limited to certain stores or countries of sale or may be sold out.

©Disney