Walt Disney and Osamu Tezuka continue to have a profound influence on the world of comics both in Japan and around the world. To discuss the legacy of these master creators, manga artist and Tezuka superfan Kotobuki Shiriagari is joined by Tezuka’s daughter and director of Tezuka Productions, Rumiko Tezuka.

A miraculous encounter with legend

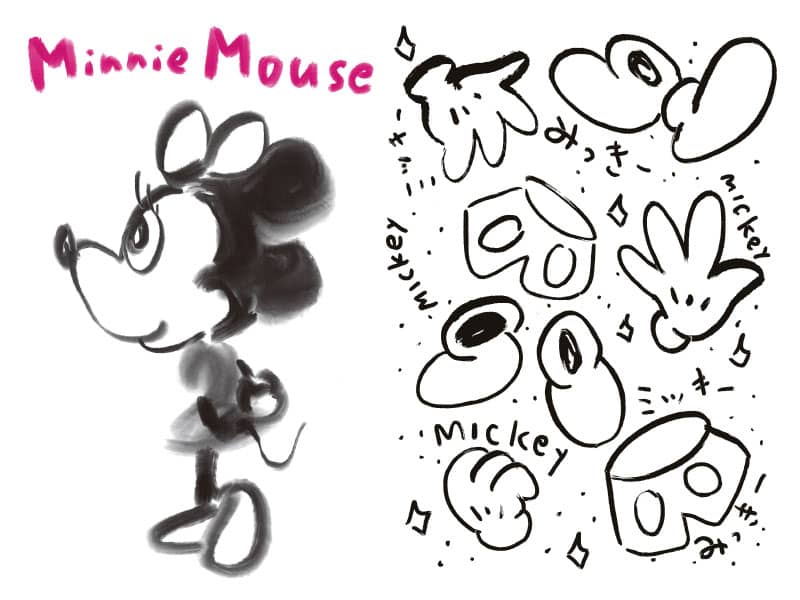

"Kotobuki: This project is sort of a milestone moment, wouldn’t you say? Not many people know that Mr. Tezuka has done drawings of Mickey Mouse. Seeing one on this T-shirt will be the first time they find out.

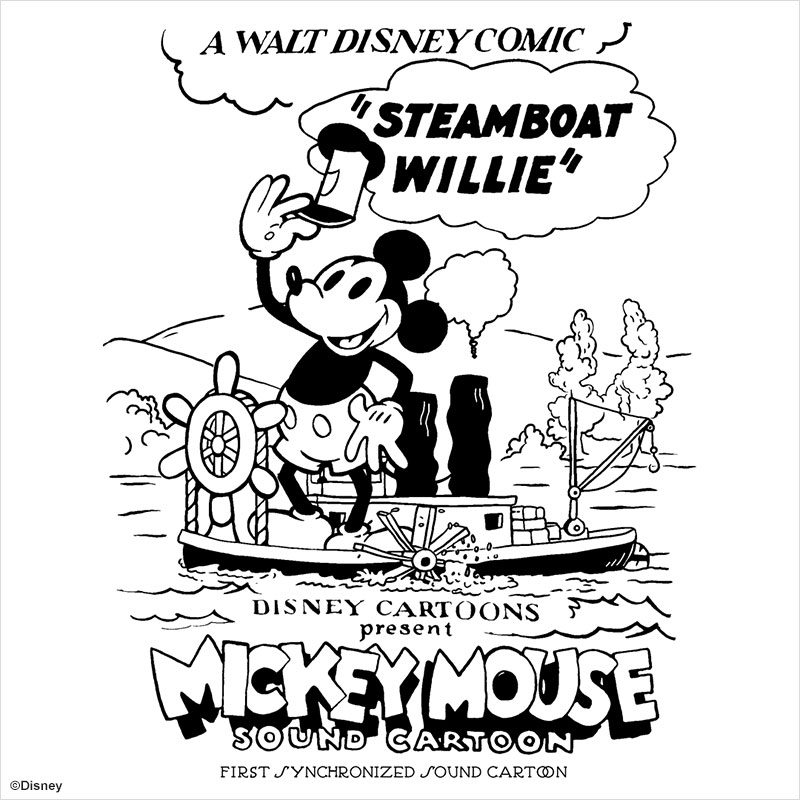

Tezuka: My father was a huge Disney fan. He first saw Mickey when he was in primary school, and he’d copy drawings of him again and again until he got the look just right. Later in life, he became friends with some of the animators at Disney and had some of their original Donald Duck artwork hanging in his study. He even met Walt Disney himself—just once—although he didn’t dare exchange more than a few words with him. To him, Disney was like a god.

K: Well, he’s captured Mickey extremely well. Nothing about the character feels off. See how lively and animated he looks? Not at all like the Mickey I drew!

T: That’s not true at all! I love yours. It’s very original.

K: You should see how many ideas I pitched. Lots of weird ones, too. After a few twists and turns, we settled on this design."

"K: Incidentally, I’ve met Mr. Tezuka—just once.

T: After your debut?

K: No, actually. This was when I was in the manga club at Tama Art University. The other members and I were visiting Sendai. We all dressed up in costumes and were taking the elevator up to the roof of the department store to attend an event. But when we got there and the doors opened, there was the great Osamu Tezuka, standing in a halo of light! Leave it to Mr. Tezuka to be completely unfazed by our masquerade and shake our hands. That was my first and last interaction with him."

T: It was? I thought for sure your paths would have crossed again after your big break. It’s well known by now that my father considered you a genius. He’d look at other artists’ work and say, “I can do that.” But he said you were impossible to duplicate. It’s a shame it took us so long to present you the Osamu Tezuka Culture Prize.

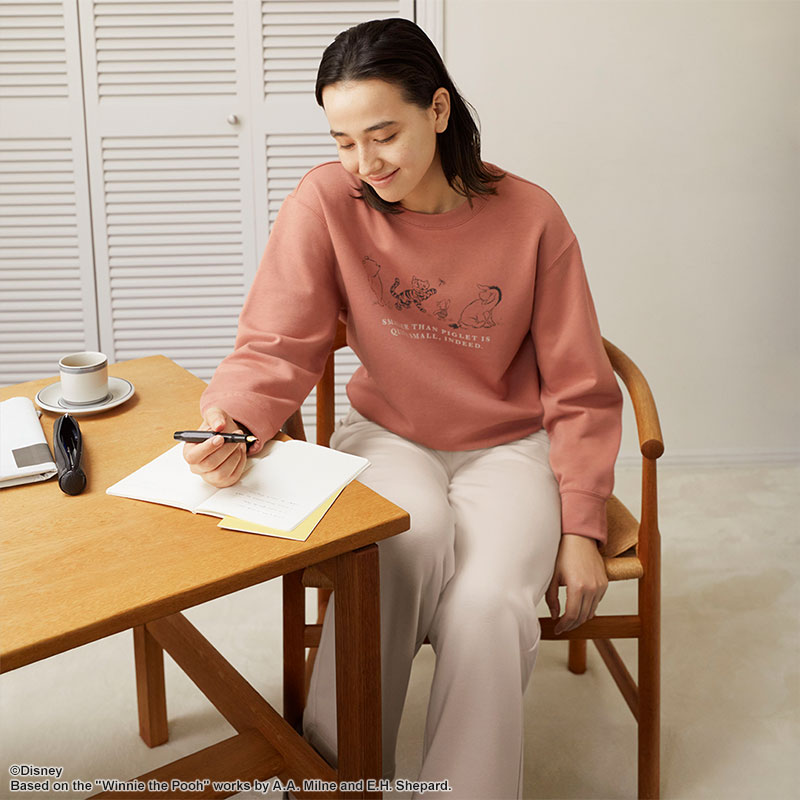

K: Oh, not at all. I was thrilled when I got it! I brought my wife and newborn daughter to the ceremony. We stayed right there at the Imperial Hotel. It was great. Not that my daughter remembers any of it! But I was truly touched. When I was in preschool, Mr. Tezuka’s manga and Disney picture books were all that I read. My parents loved Tezuka. I might have done a little scribbling in their hardcover copy of The Fossil Island.

K: I had no idea you and my father were collaborating at such an early age! Joking aside, I know you’ve stepped in to help with Tezucomi [an official Tezuka Productions project that brings together manga artists to draw tributes to Tezuka’s works].

Tezuka’s manga and the origins of kawaii

K: I haven’t improved much as an artist since then. (Laughs.) But nothing else at that age grabbed me the way that Tezuka’s comics did.

T: His style changed a lot as the years went on. In The Fossil Island era, you can see the heavy Disney influence in his drawings. Lots of characters with round silhouettes.

K: That was a key feature. People are drawn to things that are round.

T: Like babies. When people see something round and snuggly, they develop feelings of love and caring.

K: I think this “roundness” found its way into Japanese manga via Mr. Tezuka channeling Disney, because if you go further back, to the Hokusai Manga [Katsushika Hokusai’s collection of sketches of everyday life, flora, fauna, and even the supernatural], the people and animals are all bone and sinew. Definitely not what you’d call endearing! In that sense, you might say that the culture we call kawaii has its roots in Mr. Tezuka’s works. These days, we have characters who don’t even have realistic proportions. Some of these Pokémon characters are literally just heads. What’s next? You can’t get rounder than a head! Anyway, I’m certain that this cultural through line, from Disney to Tezuka to today, had a massive influence on Japanese manga. That sense of speed and dynamism, those exaggerated movements and expressions—we were given a great pictorial invention.

Osamu Tezuka “loved to draw butts”

K: I can’t put my finger on what it is, but something about Mr. Tezuka’s art has the effect of closing the distance between the main characters and the reader. Is it the eyes? He includes the whites of the eyes. Mickey Mouse has gone through both stages: one where his eyes are solid black and one where his eyes have whites. Maybe Mr. Tezuka followed suit and changed his drawing style to match the new Mickey. Today, when we talk about eyes in Japanese manga, we’re usually referring to characters drawn by artists in the shojo manga genre.

T: The “culture of eyes” in Japanese manga is really something else.

K: Right? I remember hitting a point about ten years ago when I thought my art might be getting stale. So I tried copying the eyes of characters from Death Note. I couldn’t do it. I gave up after, like, three hours.

T: That’s all? (Laughs.) Well, my father’s characters may be round and cute, but I think it’s more than that. There’s an eroticism in them, too. If you look at the cats he drew, they’re—well, maybe not sexy, but he did manage to give his animals attractive, sultry qualities.

K: True. I was probably still in elementary school when I was first exposed to The Amazing 3 [a sci-fi manga by Tezuka in which Earth is at constant war and three galactic agents arrive to investigate, transforming into rabbit-, duck-, and horse-like forms to avoid detection]. I remember having a thing for the rabbit, Bonnie. She was hot when she got mad.

T: Bonnie was the captain of the galactic agents, even though she took the form of the smallest, most vulnerable animal.

K: Another manga I read in elementary school was The Legend of Kamui. That one features a lot of animals that are exceptionally well drawn. But they looked scary. Even at that young age I could tell they were completely different from Tezuka’s animals.

T: Of course. Animals are naturally scary. Walt Disney and my father flipped that idea, imparting their animals with lovable, even sensual qualities. Around the same time, Tezuka created other manga like The Vampires where he tried to make the animals look frightening, but despite his best efforts, there’s still something lovable about them.

K: Maybe it’s the curvy hips that make them so sensual.

T: If I can just put this out there: my father was a total butt guy. (Laughs.) So much so that he always had the figurines in his study lined up with their rear ends facing out. I think that’s another thing he picked up from Disney. You have to admit Disney drew Mickey and Bambi with attractive butts. That’s why some Tezuka characters that seem cute at first glance have such strangely voluptuous hips.

To be continued next week.

©Disney

PROFILE

Rumiko Tezuka | Rumiko is the eldest daughter of postwar manga pioneer Osamu Tezuka. She oversees cross-promotions and other projects featuring her father’s works as a freelance planning producer. She also presides over the MusicRobita music label and chairs the Kichimushi Osamu Tezuka Cultural Festival committee.

Shiriagari Kotobuki | Since debuting with his 1985 comic Ereki na Haru, Shiriagari has garnered attention as a new breed of “gag” manga artist with parody at the core of his style. Notable works include Yaji and Kita: The Midnight Pilgrims. His comic Yaji Kita in Deep earned him the 5th annual Osamu Tezuka Culture Prize’s Award for Excellence.