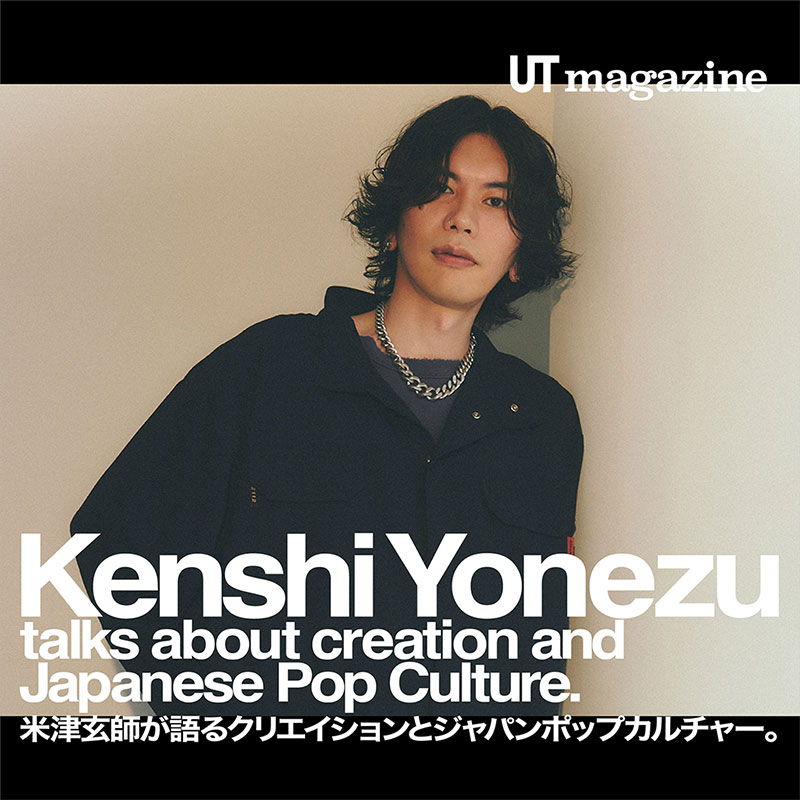

This time, for the special collaboration between UT and the Louvre, we are excited to feature the globally acclaimed contemporary artist, Camille Henrot. Her works have a unique ability to captivate both the eyes and the hearts of viewers, offering a complex, multi-layered perspective that seems to deconstruct and rearrange the systems, values, and information that shape our world. Camille, who has professed a love for museums filled with countless works "like an encyclopedia," has carefully selected pieces from the Louvre’s collection to create her own t-shirt designs. In this interview, we dive into her thoughts on the joy of exploring museums, her interest in Japan and ikebana, and her take on fashion. We began by asking about her connection to the Louvre, and as someone born and raised in Paris, she revealed it has been a part of her life since childhood.

Being from Paris, I used to visit the Louvre with my mother and grandmother quite often as a child. I remember that it seemed infinite, like there was no end. My mother was always a bit absent-minded and distracted by the artwork, so I had a fear of getting lost. As a teenager I went to the Louvre with school groups, and I recall that Géricault was the main attraction for me at that time – the costumes, the horses, the drama. I wanted to be able to draw horses like him. When I filmed footage for my film “The Strife of Love in a Dream” at the Louvre in 2012, I learned to orient myself in the museum, and gained a sense of ease within the space which is a nice feeling – no longer worried about getting lost! Now I love to visit with my own children. It’s nice to be able to share my knowledge of art history with them – and to see them discover their own favorites in the collection.

Out of all the great artwork at the Louvre, why did you choose the pieces you collaborated with for the t-shirt design? Can you tell us the stories and ideas behind all four designs?

When I would visit the Louvre with my grandmother as a child, she often pointed to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres as one of the most talented ‘line’ artists – a painter who had a very strong, crisp sense of line drawing and painting. There’s something very dynamic in his lines – they are so precise but also slightly distorted and this gives his subjects so much life.

When I looked at the portrait of Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière, I was fascinated by the strong forearm in this golden-beige glove, and the contrast with the sitter’s delicate face and the way the scarf is falling. I love the way the face is kind of flattened and the neck is extended. The shoulders fall lower and seem shrunken to the point where the face emerges like a growing plant. There’s an intensity about the way she is looking at you, similar to the Mona Lisa. We feel directly looked at from every angle due to the position of the subject’s eyes.

© 2017 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

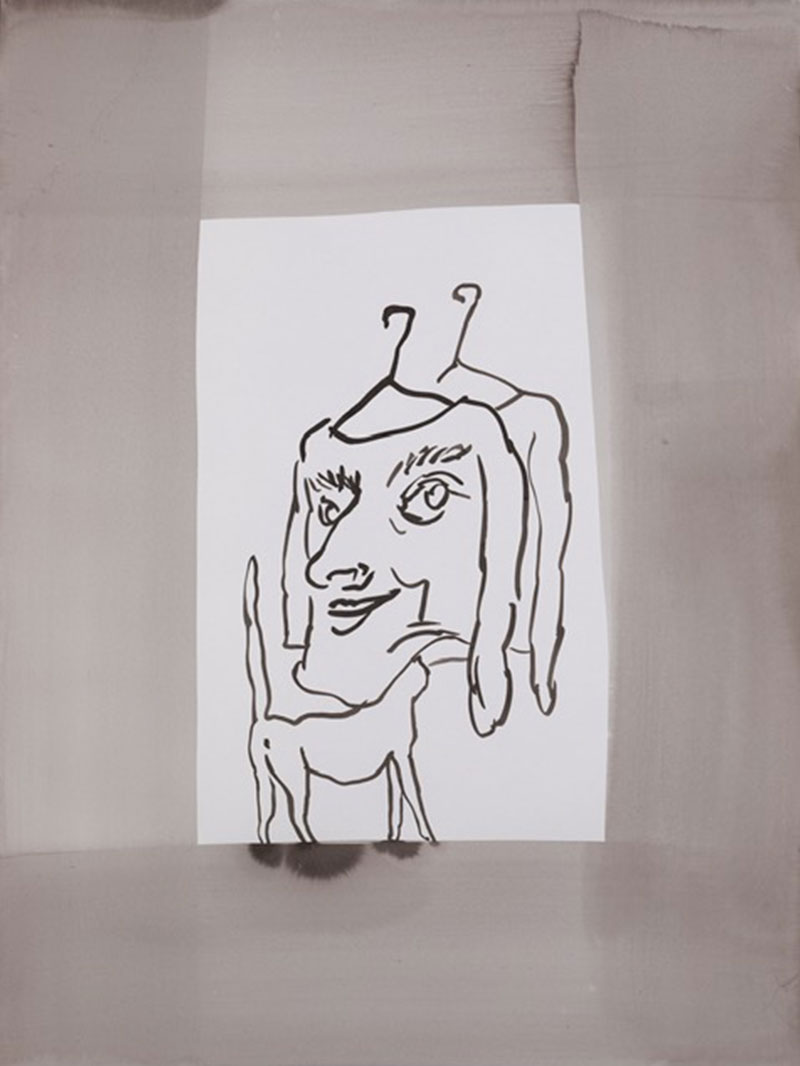

For ”François-Hercules de France”, I was intrigued by the fact that it was a painting of a child portrayed as an adult. Many princes and princesses were portrayed this way. I found a deep melancholy in his expression. He looked so lonely, so I added a dog to the design, to comfort him.

© 2011 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

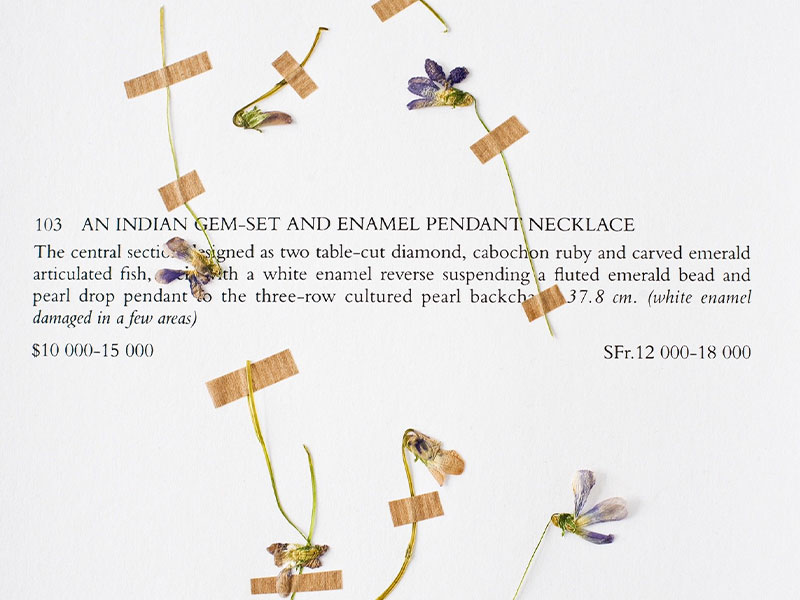

The Uniqlo artistic direction was interested in working with design elements from one of my existing artworks called “Jewels From the Collection of Princess Salimah Aga Khan”. It’s an installation of prints overlaid with collages of pressed flowers and photos of me collecting flowers on the Upper East Side of New York City. The prints are scans taken from a catalog of precious jewels being sold at a Christie’s auction by the Princess. The artwork is a meditation on a woman’s right to wealth, and the concept of value.

Camille Henrot, Jewels from the Personal Collection of Princess Salimah Aga Khan (detail), 2011-2012

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

Camille Henrot, Jewels from the Personal Collection of Princess Salimah Aga Khan, 2011-2012

Installation view, "Days Are Dogs”, Palais de Tokyo, 18 October 2017 - 7 January 2018. Photo: Aurelien Mole.

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

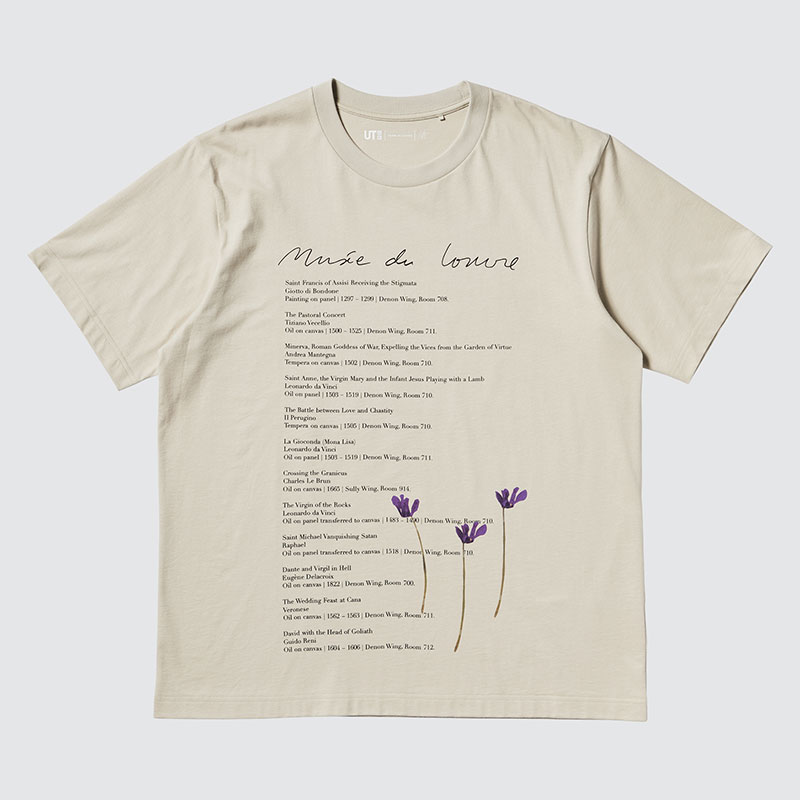

For the T-shirt design, we used a list of famous artworks in the Louvre collection, which I found doing a Google search online for the most famous artworks in the collection. I’ve always loved looking at ‘best of’ lists online – the contrast between how random and subjective the list is, with the authority and assertion of the claims it makes has always amused me.

What do you enjoy the most about visiting museums in general?

I’m always up for a visit to a big, ‘encyclopedic’ museum like Le Louvre or the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Because their collections are so wide and diverse, I always find something that answers or solves a certain aesthetic problem that I’ve been contemplating. For instance, drawing feet is really difficult, especially from the front, but the ancient Greeks offer a really elegant solution for this. Or, I’ll be looking for references of animals in sculpture and I stumble upon a miniature of a cow or a dog from ancient Egypt, and even though it’s small scale, they immediately offer an interesting solution for the way the legs fold when seated, for example. Or colors – sometimes I grow tired of the colors I use and then I see a painting of a lady in a mauve fabric with a salmon pink background – colors that I never would have thought to combine. Or how to make lips look alive – sometimes the contour of the lips is never really defined, and the color of the lips is actually more integrated into the face than we would have expected. A contour can make a face look more stiff, but a blurred edge makes the subject feel more alive and more human. I always find interesting cues and directions for my own work in these kinds of museums.

In 2015, you exhibited ”Is it possible to Be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers?” at the Louvre. What motivated you to present this work at that time?

Installation view, "Is It Possible to Be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers?”, La Triennale: “Intense Proximity”,

Palais de Tokyo, 20 April - 26 August, 2012. Photo: Fabrice Seixas.

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

Camille Henrot, “Coyote Stories”, Mourning Dove, 2014

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

Installation view “Camille Henrot: Stepping on a Serpent”, Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, 16 October - 15 December, 2019. Photo: Go Itami

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

My series “Is it possible to Be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers? ” is a collection of ikebana arrangements presented in groups. Each arrangement is modeled after the memory of a book I read, and includes found materials and organic elements in various states – some decayed, some fresh and needing to be replaced throughout the course of the exhibition. I was honored to present some arrangements from this series for the exhibition “Une brève histoire de l’avenir” at Le Louvre – a collection of contemporary and historical objects about the human conception of time and the past. Because this series deals directly with my own memory, and the reconstruction and representation of memory, it was a great opportunity for me. I’ve long been fascinated by the ways we, as humans, develop systems for organizing the chaos of life – my exhibition “Days Are Dogs” at Palais de Tokyo in 2017 was all about psychological associations and feelings we have about the days of the week – an entirely man made system.

Why were you inspired by ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging? Did your ideas on ikebana change when you visited Japan?

I visited Japan long before I started to work with ikebana flower arranging. Japan was a place I had dreamt of visiting for many years. As a child in the 1980’s, I was very immersed in the Japanese manga culture, watching cartoons on TV. The TV, my pencil and paper were my babysitters [laughs]. My mom also had Japanese prints on the walls at home when I was a child. My curiosity to visit Japan was nurtured from a young age.

In 2005, I was invited to present work at the Hara Museum in Tokyo, and I stayed for a couple of months. Funnily enough it was not in Japan that I became interested in ikebana. In 2010, I had just moved to New York City, and I bought three books about ikebana from a street vendor. One of the books was about the Sogetsu School of ikebana, and I became deeply enamored with the principles – that this form could be practiced anywhere, anytime and by anybody. I started to collect found objects in the street, and bought some flowers and plants, though my options were limited due to a tight budget. I started doing this for almost two years between 2010 and 2011, making an ikebana arrangement every day to honor the memory of a book I had read. It was a melancholic practice because those books were held up in customs for almost a year while I was moving my life to New York. My practice evolved when I met the incredible ikebana master Rica Arai in Paris, on the occasion of the Palais de Tokyo Triennial in 2012, “Intense Proximity”, curated by Okwui Enwezor. Rica taught me a lot of different techniques from Sogetsu School during the installation of my works in the Triennial. Then, my practice evolved further when I did a solo show in 2019 at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, curated by Shino Nomura, who introduced me to Katei Motoe and Kazuko Nakada of the Sogetsu School. I was very honored, and also very anxious to present ikebana in Japan.

Was there anything else you found interesting during your visit to Japan?

Everything! If I was to go deep into detail this would be a very long answer. To be honest, I experience a feeling of total bliss when I’m in Japan. When I'm not in Japan, I spend a lot of time longing for Japan, making lists of things to see next time, reasons to go, things to buy. The gardens are so interesting; the ways the trees are cut… Japan also has the best fashion, the designs are the only ones I never grow tired of and the quality is better than anywhere else. Many of my studio tools were purchased in Japan – I love Pigment Tokyo, the blades, and also the paintbrushes from Seishind.

I was already a bit like a cat before visiting, and Japan felt so adapted to my sensitivities – I love the food and how the essential nature of a taste is preserved; nothing is too strong or overly complex. The noise is also very controlled – the subway sounds can lull you to sleep! And of course, Japanese prints are a huge inspiration for me, the strength of the line in calligraphy, etc. Japanese cinema is also so good. I know it probably just as well as French cinema. The list goes on…

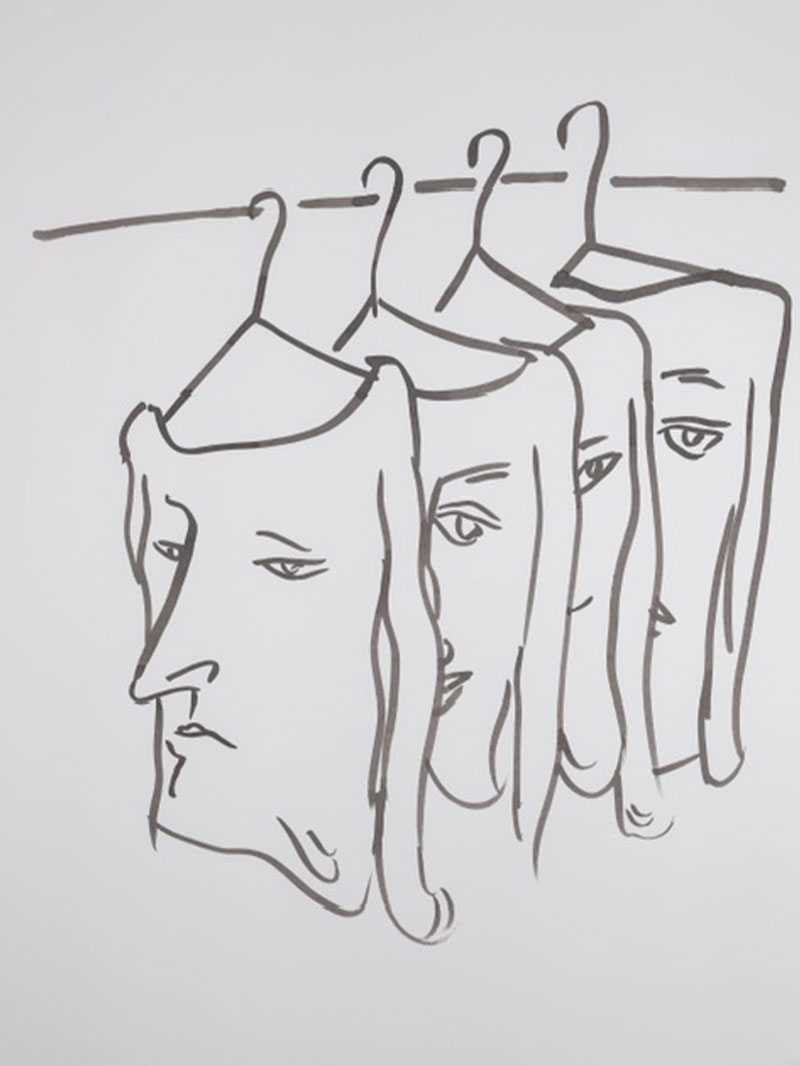

It says that the drawings exhibited in “Stepping on a Serpent” at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery in 2019 were inspired by “the unique characteristics of clothing that creates depth when worn on the body while becoming completely flat when taken off”. Can you share your thoughts on these drawings?

Camille Henrot, Resting Faces, 2018

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

Camille Henrot, Please Tell Me Who I Am, 2019

© ADAGP Camille Henrot. Courtesy of the artist, Mennour (Paris) and Hauser & Wirth.

Yes, there were drawings from the series ”Identity Crisis” in that exhibition. This series was about the contrast between clothes hanging on a hanger or flat on a table, and how the patterns can change when worn on the body – a certain play with 2D and 3D but in drawing. That observation was related to my thinking about the role of clothes in society and how they can mirror questions of identity, ‘fitting in’, and inadequacy. This was one of the ideas of this series.

What is fashion/clothing to you? Does what you wear affect the way you think and act?

Fashion is very important and inspiring for me. I grew up in an environment that was very attentive to fashion and elegance. Very early in my life, I asked to have a subscription to Vogue magazine, both French and Italian Vogue, and I thought I would grow up to be a fashion designer. I still have a lot of books of sketches for fashion designs. In the everyday sense, fashion brings me a lot of joy, whether I’m looking for a new association or spirit, or working on adjusting the look to my mood and how I’m feeling that day. It sounds futile, but just looking at fashion and discussing it with friends, or seeing an interesting outfit on someone in the street, is very entertaining for me. It’s like having sugar in your tea. Maybe it relaxes me, like the way some people enjoy sports or discussing the performance of their favorite football team. I love the newness of it, the way it’s constantly changing and renewing, like running water. I don’t have an obligation to dress well in my day to day life at the studio, but when I go to special events, it’s fun for me to step out of work and into a space of play. There’s a clear distinction. It means I can become somebody else.

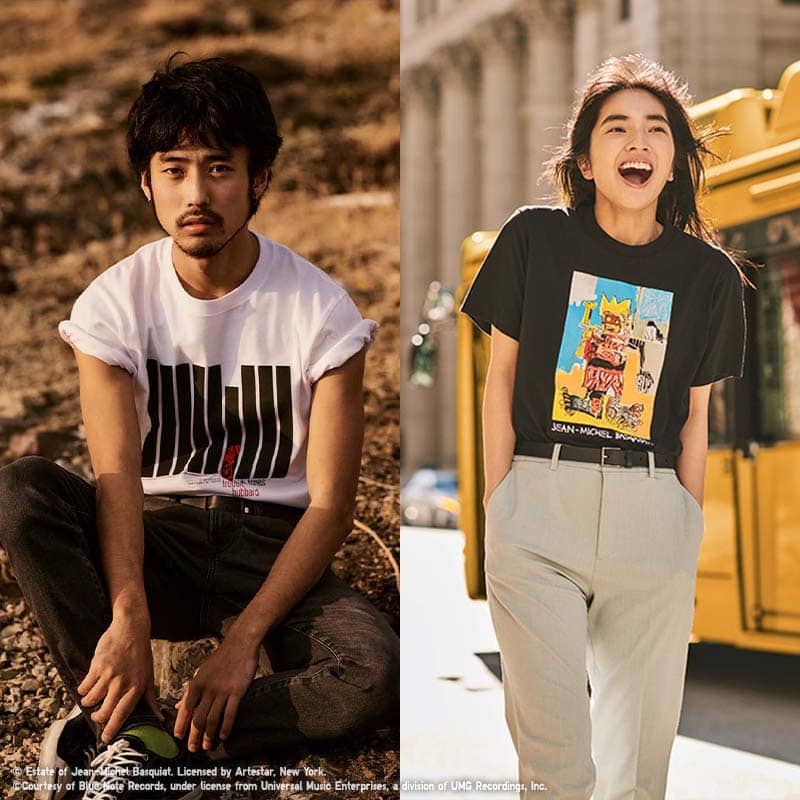

It seems that having your images mass printed in the production system is the opposite of having authenticity as a work of art, but how do you feel about your work being “worn” by others in the world? Intimacy seems to be a recurring theme in your work; do you think wearing a piece of art gives us different ways to experience art?

I’m sure the experience of wearing an image of an artwork creates some kind of link in people’s minds, yes. You notice this very easily with children – it seems they like things because they’ve seen them before or they’ve managed to recognize them. Wearing an image of an artwork is not a guarantee of a deep connection with art, and I wouldn’t have the arrogance to say that my works will provide that – but I suppose the designs do serve as an entry door or advertisement for the experience of viewing art. I’m most looking forward to seeing the shirts in 10 or 15 years after they’ve been washed countless times, when the fabric changes and the colors fade – out of people’s sheer love for the object. There is nothing like the comfort of a soft, well worn T-shirt, even if it has a couple of stains.

With social media feeding seemingly quick, simple answers for everything, people are becoming increasingly intolerant of uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity. You’ve mentioned the importance of artists protecting “a space of nuances and contradictions.”*2 Why do you think this is important? Do you have any advice on how to enjoy being suspended in the moment of the unknown, especially when people are afraid of making mistakes and not having immediate answers?

It’s very important to build spaces where complexity can be contemplated and understood without urgency. Especially in an election year in the US, I feel there’s too much emphasis on urgency, binary oppositions, take-away opinions and simplifications. People’s attention spans have reduced drastically. I feel worried about this when I think about the future, about my children’s future. Activities like ikebana, painting, drawing, sculpting, reading are restorative and bring peace of mind. They allow you to think for yourself. They allow our thoughts to flow without a predetermined direction, bringing us closer to meditation, perhaps. Being in this mode is very important for the quality of your judgment, and for one’s mental health. It feels increasingly difficult to create that space, but also increasingly necessary. It’s precisely because digital culture is eating our time that we require more strength and discipline to protect our boundaries. I believe artists, writers and musicians can help to create these spaces.

Are there any ideas or topics in the world that you are particularly intrigued by at the moment? How do these influences manifest in your work? Are there any upcoming projects or exhibitions you’re excited about?

I’ve been spending a lot of time with the idea of care work and how it has been devalued historically. Last year, I published a book of essays called “Milkyways” with Hatje Cantz. Overall, it’s a meditation on the conflicts and opportunities that arise in being both a parent and artist, in a political and artistic sense.

My next exhibition, opening at Hauser & Wirth in February 2025, will be more focused on education and the concept of domestication – how culture is transmitted, how the ‘norm’ is forged; how it’s sculpted into us, and how we are then sculpted into society’s norms. What do we lose and what do we gain? There will be a series of paintings called “Dos and Don’ts”, made combining different techniques of painting, collage and printmaking, taking inspiration from both historical and modern books on etiquette and social behavior. I’ve always been interested in the way humans develop rules and systems – both for what they offer us, and also how we can break, critique and subvert them.

I’m also working on new sculptures inspired by the abacus and calculating systems. It’s interesting to be returning to abstract sculpture after doing mostly figurative works in recent years – though to be honest, the categories of abstract and figurative lost their distinction and relevance to me some time ago. I can see life in any object very easily. I have always felt like the purpose of sculpture is actually to animate, to bring life to an object. I just came back from Rome and Naples, where I visited some of the Baroque artworks that made a huge impression on me years ago. I was reminded how important it is that sculpture captures a sense of movement not only in its form, but in relation to the observer in their various positions. I just made a sculpture of a cat with piercing eyes, and I was reminded of Caroline de Rivière’s portrait and the Mona Lisa. I wanted the sculpture to feel like it was following you, looking at you. The cat is an image of peace and rest, and a meditative attitude towards life. It’s an animal spirit that I want to relate to, these days.

Camille Henrot|Stepping on a Serpant [EXHIBITION] Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

https://www.operacity.jp/ag/exh226/e/exh.php

*2 An Interview with Camille Henrot by Jason Farago, Even Magazine

http://evenmagazine.com/camille-henrot/

Interview and editing by Kanoko Tamura (Art Translators Collective)

PROFILE

Camille Henrot|Born in 1978 in Paris (France), CAMILLE HENROT lives and works in New York City. Camille Henrot is one of the most influential voices in contemporary art today and has developed a critically acclaimed practice in film, painting, drawing, bronze, sculpture, and installation. Henrot draws upon references from literature, psychoanalysis, social media, self help and the banality of everyday life to question what it means to be both a private individual and a global citizen in an increasingly connected and over-stimulated world.

© Camille Henrot

Release dates and prices may vary. Some items might be limited to certain stores or countries of sale or may be sold out.