Daido Moriyama has been wandering the streets of cities around the world since the 1960s, exploring the possibilities of the humble snapshot. His renowned Stray Dog, Misawa and other works have now made it into our UT collection. We talked to Moriyama about his thoughts on photography.

The joy of seeing one’s art on a T-shirt

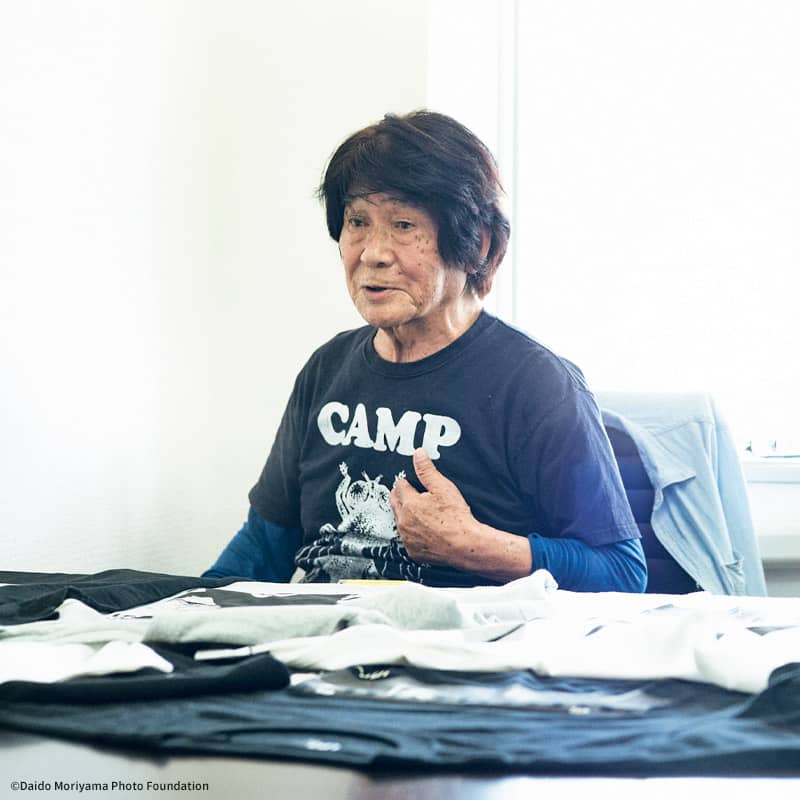

“I love it,” says photographer—or cameraman, as he prefers to be called—Daido Moriyama. It’s a response to a question about how he feels about his photography being incorporated in a UT collection—perhaps a surprising reply for someone who has cultivated the image of a lone wolf.

“I’d much rather have my work on a T-shirt or clock than framed in a gallery,” he explains. “Once it’s on a T-shirt, it becomes as anonymous as the signboards and cinema posters I photograph around town. The person wearing the shirt doesn’t care who took the picture, and that’s perfect. They saw the image, liked it, and made the decision to wear it—that makes my day. If I see someone wearing one of these shirts, I might even go over and shake their hand!”

Moriyama takes a closer look at his UTs. His favorite? The Hand T-shirt.

Not many artists would have the confidence to let their work be disseminated independently of their name—but then, Moriyama has spent decades developing a powerful style that is unmistakably his. This style is already apparent in the earliest work featured in this collection—Stray Dog, Misawa. He shot this photograph in the city of Misawa in northern Japan, known for the US military air base there.

“I was in Misawa taking pictures for my regular column in Asahi Camera magazine,” Moriyama recalls. “I like that distinctive vibe you only find in cities that host US military bases. One morning, I stepped outside my hotel and saw this stray dog, and I immediately assumed it had been abandoned by a US soldier. It was staring at me with this shady look on his face. I took a couple quick shots, but I didn’t realize what a great expression the dog had until I developed the photographs back home and enlarged them. One of the pictures got a two-page spread, and people loved it. MoMA and other places around the world started contacting me. I think people around the world have seen this work more than anything else I’ve done.”

Some critics have noted the similarity between the image of a stray dog wandering the streets of a city, turning its sharp gaze to everything it comes across, to Moriyama’s approach as a cameraman. Could Stray Dog, Misawa be a self-portrait?

“Not intentionally, but because I’m always restless and want to explore every alley no matter where I am, people do often tell me that I’m like a stray dog,” Moriyama says. “So maybe, subconsciously, I was taking a self-portrait.”

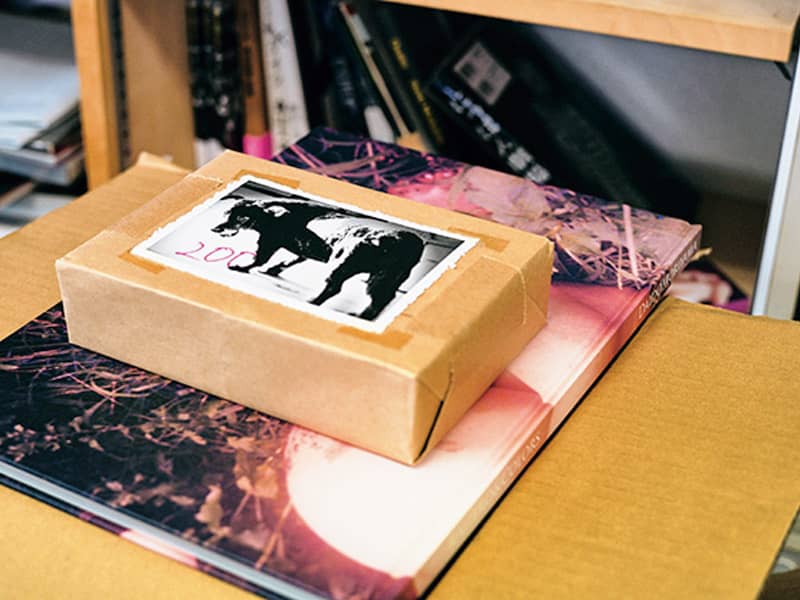

This is the original Stray Dog, Misawa. “With many of my works,” Moriyama says, “I take a picture and don’t think anything of it, only to be taken by surprise by its impact when I develop the photograph. This is one that really caught me off guard.”

Stray Dog, Misawa has been featured in many products over the years, including this postcard.

“A photograph is just a piece of the world.”

Stray Dog, Misawa has been significantly trimmed for the T-shirt, but Moriyama is fine with the changes. In fact, such editing fits his philosophy of photography.

“I’m not saying anything can be trimmed willy-nilly,” he says, “but for example, when developing the original, I trimmed it to make it look like I was closer to the dog than I actually was. A photograph is just a piece of the world. No matter how wide the shot, you can only capture a slice of what you see. So for me, trimming is not a problem.”

Before getting into photography, Moriyama worked in graphic design. He left the industry early, realizing it was not for him. But some of his experience as a designer influenced his views on trimming.

“The studio where I was working had magazines and photo books from around the world that were full of images that had been stylistically trimmed,” Moriyama says. “I read many of them, and I think that style stuck with me, which is why I have no problem with trimming”. “William Klein’s New York (1956) also had an impact on me. He trims even more than I do—sometimes to the point where I think he’s gone too far. But even then, I can never think of a single reason why he shouldn’t have done that. I like that sense of freedom in his work, which is why New York is kind of like my bible.”

Different cities, different streets, but always the same approach

Speaking of New York, another work featured in this UT collection is NY, which Moriyama took while visiting the city at the behest of the artist Tadanori Yokoo, around the time that Stray Dog, Misawa was published. The work shows that no matter what city Moriyama finds himself in, he does not change the way he photographs it.

“I always have the same approach: take as many snaps as you can,” he says. “If it’s a city and there are people, I will dive in, looking for those moments when my interests and the city’s interests cross paths. Whether I’m in Tokyo or New York, it doesn’t matter. Sure, the scenery might change, but I don’t really think about that. I’m not interested in the character of a place, with the exception of Tales of Tono. I don’t really change my approach no matter where I go. When I was photographing highways, I thought, ‘It’s just like Tokyo but longer and narrower.’ [Laughs.]”

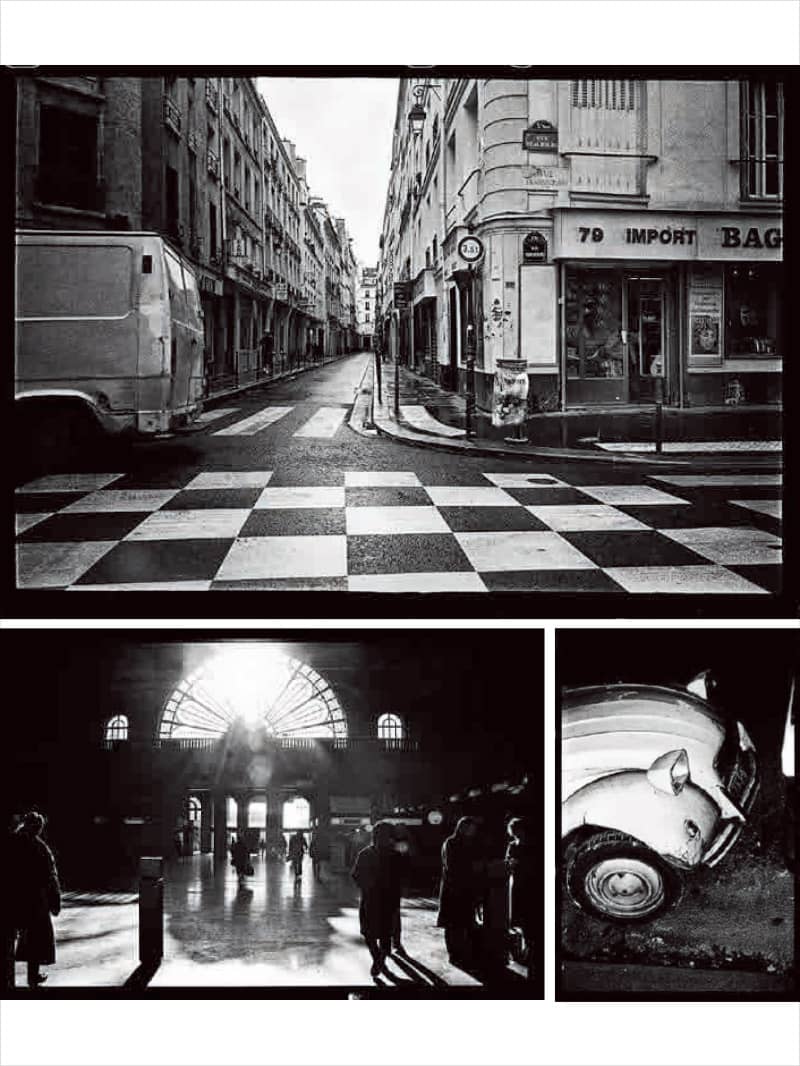

Moriyama’s Paris also attests to his hardwired approach. But he finds it difficult to photograph the city, and he jokingly blames it on Eugène Atget, the French photographer who produced innumerable images of the city from the late 19th to the early 20th century.

“No matter where you take your picture, it ends up looking like an Atget photograph,” Moriyama says. “I’m sure Paris has changed since his time, but there are still so many old buildings. Just about every alleyway is straight out of an Atget photograph. The only reason I published Paris was because I thought I was able to capture something different from Atget.”

For a few years beginning in the late 1980s, Moriyama frequently traveled between Tokyo and Paris to try to set up his own private gallery. The plan failed, but he did snap these and other photos that compose his work Paris, which was published in the photo book Paris Plus.

Captivating at first glance: The criteria for Moriyama’s subjects

Moriyama may be better known for fearlessly pointing his camera at the perfect strangers he comes across while walking through town, but he has also often taken pictures of himself—shadows, mirror reflections, or parts of his body. A couple of these works—Hand and Shadow—made it into this collection.

“People think I’m being narcissistic, but it’s not that at all,” Moriyama says. “I saw something that looked neat, so I took a picture. I took Hand because I just happened to be working on a balcony that offered me a clear view of distant skyscrapers. In that sense, there’s no deep meaning in my photography. I’m only interested in what’s right in front of my eyes and the things I haven’t yet encountered. I don’t walk through a city so much as I hurtle through it, looking ahead the whole time. And in the end, I feel like I captured everything that I encountered. In reality, I probably missed a lot of things. But with my approach, I end up feeling like I accomplished everything I set out to do.”

The skyscrapers in Hand stand in Shinjuku, an area in Tokyo that Moriyama has photographed more than any other location.

Hand was published in the photo book Daido Moriyama: Terayama, which pays homage to Supotsu-ban Uramachi Jinsei (Backstreet life: The sports version), a collection of essays written by Moriyama’s friend and avant-garde artist Shuji Terayama. The composition, with Moriyama’s hand in the foreground and skyscrapers in the distant background, is striking.

“Shinjuku is a lot like me,” he explains. “Apologies to the people of Shinjuku, but it’s sleazy. If I went to a quiet residential area, nothing interesting would happen. In fact, I went to one two years ago and was only able to take one photograph. And I forced myself to take it! [Laughs.] I’ve traveled to many places, but I always go back to Shinjuku. People ask me if I ever get bored of the place and, well, yeah. [Laughs.] But what can I do? My feet always take me there. This place has had this effect on me ever since I first traveled to Tokyo from Osaka and exited Shinjuku Station.”

Shinjuku has changed a lot since that first encounter. However, Moriyama isn’t particularly nostalgic about the area’s past.

“Sure, Shinjuku has changed, but so have other parts of Tokyo, and even more dramatically,” he says. “But it’s not like I can do anything about it. Photography only reflects the present, so my only choice is to capture the present. I can bear these changes more than I can bear the idea of not photographing these areas anymore.”

Just as he has always done, Moriyama continues to walk through the city to capture its living, breathing streets and its people, just as they are right now—and not even Covid-19 has slowed him down.

“I stayed home for the first two days of the first state of emergency,” he says. “On the third day, I left the house. I had to. Photographers can’t work remotely. Of course, there were fewer people out than usual. But that’s fine. That’s the present as it really is.”

Moriyama has a hard-boiled look, complete with a cigarette in hand. Here, he is wearing a reissue of a T-shirt once sold by CAMP, the gallery he used to operate with a number of other photographers.

Stray Dog, Misawa has been trimmed for this UT to focus on the dog’s unforgettable, murderous expression.

For decades, Moriyama has held his camera with this very hand. “Since it’s from close to twenty years ago, my hand still looks young,” he laughs.

All T-shirts in this collection feature Moriyama’s signature printed on the sleeve, except for the Paris shirt, where the signature is emblazoned on the chest.

The NY shirt features the negative of the titular work. Printed below is “’71-NY”—the title of the photo book featuring the original.

Shadow features Moriyama’s own shadow being cast on a tire abandoned on a beach. Although he vividly remembers the shoot, he can’t recall where he took the picture.

PROFILE

Daido Moriyama | Moriyama was born in Osaka Prefecture in 1938. After assisting Takeji Iwamiya and Eikoh Hosoe, he became a freelance photographer in 1964. He has exhibited his work around the world and has published numerous photo books, including Japan: A Photo Theater, Farewell Photography, and his Record series.

©Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation